Understanding what drives human behaviour: Emteq’s wearable tech in immersive environments

“If we can understand emotions, we start to develop an understanding of what drives human behaviour.”

— Graeme Cox, CEO Emteq

A pioneer in emotion-sensing through facial wearables, Emteq was founded just two years ago and is currently operating from offices in the Sussex Innovation Centre, based in the University of Sussex. It’s start-up period has been largely spent in R&D, building both hardware and software that has never been built before, confirms CEO Graeme Cox, and it has already requested several patents.

Emteq’s unique hardware machines and software servers are designed to read the facial expressions of the wearer, evaluate the data of that expression and extrapolate its emotional intent. In simple terms, they are making pairs of glasses that can read their wearers’ mood.

“Emotions drive our behaviour and how we feel affects our actions, affecting how we interact, how we develop, how we learn or fail to learn,” explains Graeme. “This is very important information to understand because if we can understand emotions we start to develop understanding of what drives human behaviour. And our facial expression is the most credible way to read this.”

While this potentially ground-breaking technology clearly has many applications – markets currently listed on Emteq’s website include health, VR and performance monitoring – the company is currently focusing on the health and wellbeing aspect of the technology. There are a number of ways that eyewear can produce information on important health issues in a way that nothing else can, explains Graeme. And because glasses actually sit on the face, they are obviously the easiest way to read the face rather than having the user look self-consciously into a camera.

“Single purpose glasses are central to our use case,” says Graeme. People are used to wearing glasses, both to correct vision and in certain situations such as swimming. In 10 years’ time we will all be wearing glasses, as they provide the most simple form of direct human augmentation.”

What technology is used?

The technology is built on established scientific research, which began with Charles Darwin’s study of emotions in the 19th century. Psychologists later pioneered the research of facial expressions of emotions, principally using images. Facial expressions are generated by the contractions of muscles and by using Electromyography (EMG) electrodes that identify muscle activation, it is possible to pick up even micro expressions which are not observable to the eye.

We have evolved as humans to intuitively understand the motivations of others by interpreting their facial expressions, we read emotions from the faces of those around us all the time. And now Emteq is taking that several steps further by digitising facial expressions and using artificial intelligence to interpret them.

Funding from Innovate UK for the company’s FEDEM project allowed them to merge biometric arousal data with expression data, proving they can read the correct emotions each time. “Expression itself is not enough,” Graeme explains. “Stony faces don’t reveal as much as expressive faces and sometimes a smile may mask negative emotions. Also, there is only one positive expression – a smile – but many negatives.”

Instead, measuring arousal in terms of heart rate and body heat demonstrates levels of excitement and energy. High energy levels combined with a positive expression demonstrates genuine joy or excitement, while low energy and a negative expression denote general dissatisfaction. High energy combined with a negative expression points to anger or stress. The findings have been scientifically tested by Professor Stephen Fairclough of Liverpool John Moores University, who carried out a study using Emteq’s kit, proving that the correct emotions were being recorded.

Building trust and finance

Emteq’s close links with several academic institutions and leading health bodies are essential to their work, and include partnerships with Nottingham Trent University, the University of Portsmouth, Queen Victoria Hospital NHS Foundation and the NHS National Institute for Health Research.

“It’s fundamental that we use academic researchers for our work, it’s how we move forward and we are currently co-funding three PhD students in Bournemouth, Portsmouth and Liverpool,” Graeme reveals. “These programmes allow us to work with professors who are leading lights in their fields and are also helpful in securing funding. The fact that we have highly skilled bodies working with us makes us very credible.”

Funding has so far come in the form of founder and angel funding to the tune of £600,000, as well as one million worth of grants, including the Innovate UK financing.

How does the technology work in practice?

Emteq is currently working on a number of pioneering projects in the health sector. This includes a programme to treat facial paralysis, funded by the National Institute for Health Research, that will launch next year. Part of the rehabilitation after facial palsy involves exercising the face in front of the mirror but this has a poor success rate, as people with facial palsy don’t like looking at their faces. It’s an unfortunate fact that 40% of facial palsy cases have lifetime effective results, and this is partly due to the lack of progress made with exercises in the early stages.

Emteq’s system enables patients to do exercises in gamified way while wearing glasses, by looking at an avatar on their phone, rather than their own faces in the mirror. The information provided is taken into the cloud and distributed to medical clinicians who can see if the patient’s recovery is progressing at the correct rate. As early intervention is critical in facial palsy, this innovative approach, an alternative to quarterly clinical visits, should improve positive outcomes and the first patient trials are scheduled for 2018.

Project ALERT, for which Emteq have been awarded an Innovate UK grant, investigates the measurement of fatigue through glasses, using research gained on eye blink data from previous academic studies. Devising an algorithm to predict the onset of fatigue from blink patterns, Emteq is currently looking for partners to develop a test system and is in conversation with car manufacturers and airlines. “We have the technology for this,” Graeme confirms. “Now we need to monetise it into a pair of glasses and so we need a case study. This is a valuable piece of technology and unique in the market, we’re just waiting for the right opportunity to drive it forward.”

A new project, SEEM, started in November 2017 and will run for 18 months. Working with the medical teams treating Parkinson’s patients in UK, Emteq is investigating how their glasses can monitor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease to minimise those symptoms and improve the quality of life for patients. With 14 different types of Parkinson’s identified, finding the right drug for each patient is a matter of trial and error and can take a long time in a medical system that only sees patients every few months.

However, measuring symptoms on a daily basis is possible through the Emteq glasses so the team is collecting data and working with leading researchers to determine if changes in data can be used to measure onset or regression of symptoms. This will provide a clinical platform to diagnose if the correct medication is being prescribed and the patient is getting the right intervention.

Graeme adds: “It will be three years at least before we can commercialise the project and start to roll-out its practical implementation but this could be a very important development in the treatment of Parkinson’s”. The main goal of this study is to gather the intelligence that will gauge Parkinson’s symptoms directly, with an important stretch goal of building diagnoses using machine learning on huge amounts of collective data.

Building the necessary skillset

Other than the voice analysis technology required for the Parkinson’s SEEM project, using company that has done extensive research on this, all of the necessary skills required for the projects to date have been hired in house by building, what Graeme describes as a “team of very clever people”. Working with highly complex systems, the team have built two levels of software, for both real-time data interpretation and offline examination using detailed analysis from the cloud. It’s this deeper analysis, explains Graeme, that provides the real benefits.

But it hasn’t always been easy, as Graeme’s business partner and co-founder of Emteq, Dr Charles Nduka, explains: “They call it HARDware for a reason – developing physical devices is difficult. Small changes in the physical design or in the sensor may require adjustments in the firmware, software, algorithms or interface.”

What other challenges have they encountered?

The main challenge, according to Graeme, has been one of scalability. “We are tackling very complicated areas of research, building completely new and original ways of doing things and there is the challenge of commercialising that work. In our first two years, we’ve been completely engaged in scientific research but now we need to demonstrate our commercial ability. We’re are not a research foundation, we’re a business, we’re taking cutting edge science and taking it to market.”

Monetising the market

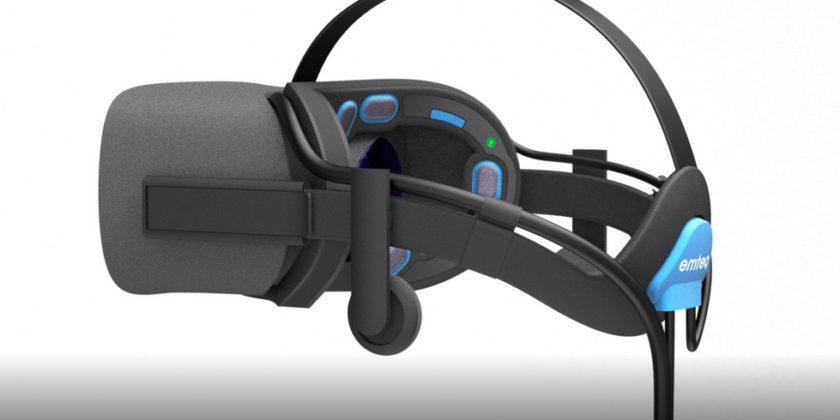

Their system has so far been integrated into two of the leading VR headphones on the market, including the Oculus Rift. Emteq has demonstrated that it is possible to move expressions and emotional responses into a VR environment, with a personal avatar that expresses itself in line with its user. Taking this personal response mechanism into a game engine adds an extra dimension to the game but also has a very important research aspect. Game creators can use the data provided to gauge how users are responding to their game, to see what works and what doesn’t.

What does the future look like for wearable tech in the immersive technology space?

“We believe that personal wearables are the next major advancement in the technology world”, says Graeme. “Just as screens migrated from the outside world into our homes – from screens in the cinema to TV screens in our sitting rooms, computer screens on our desks and phone screens in our hands – the next step is screens on our faces.” And with glasses providing a means of directly interacting with our primary sense, vision, placing a screen, between our eyes and the world is the next leap forward, according to Emteq. (With the side benefit of freeing up our hands in the process.)

With augmented reality the obvious way to push this trend forward, Graeme points to the fact that Apple, Google and Samsung are spending hundreds of millions of pounds building AR technology as the proof of its impending importance. Apple’s face tracking in the iPhone 10’s ARKit is just one example. “Finding the big money projects is the surest way of telling where the future trends lie, and AR is going to be huge,” he says.

“We are the leaders in glasses technology right now. Today 64% of people in UK wear eyewear to correct their vision, this percentage will increase substantially in the next five years as people start to wear them for other purposes. In fact, five years is the conservative view, it could be as little as three – but five is what we are building our company towards.”

And in the immediate future, the company will start to work on its first non-health project, building a kit to capture emotional responses. It will take the form of a university research study and will also link with a market research company.

“We’re pushing the boundaries on this, we’re the only company that is in viable position to collect adequate experiential data from glasses. Our data sets will comprise the largest facial biometric resource in the world and we could be world leading resource for experiential data that will be incorporated into Google’s systems, as well as other big players in this market. We’re working at the cutting edge.”

— Graeme Cox

Words by Bernadette Fallon